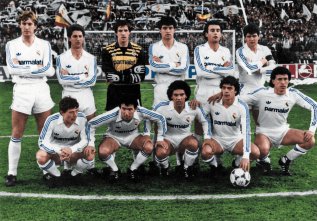

It would not be stretching a point to say that the ‘Quinta del Buitre’ of the late eighties changed the face of Spanish football, planting the seeds of what was to come in the following decades. After a long spell in which hard work, courage and fighting spirit had become the arguably limited values of Spain’s approach to the beautiful game, four kids from Madrid and one from Huelva brought flair to the table, played as though no goal difference was big enough, won European competitions after years of drought and made many believe that the “Furia Española” tag had indeed become obsolete. Heck, even Pep Guardiola states that the Quinta was Real Madrid’s best version ever.

Rafael Martín Vázquez, Manuel Sanchís, Jose Antonio Pardeza, Jose Miguel González “Michel” and, of course, Emilio Butragueño accelerated the evolution of the modern game in Spain and educated a new generation of Spanish fans into the creed of ball possession and attacking skills as the most effective way to win. This is a summary of their Real Madrid career from the eyes of a fan lucky enough to have started watching his football exactly at the moment they took La Liga by storm.

1) 28th of November 1983: Castilla 4 – 1 Bilbao Athletic – The buzz is fully justified.

In the freezing cold winter of 1983, most football fans in Madrid – including the non-madridistas – were well aware that something huge was happening with Castilla, Real Madrid’s youth team. Not only had the squad been winning most of their matches by huge margins, they had also done so in such a fashionable style that large crowds started to gather in the old Ciudad Deportiva, Real Madrid’s training ground and Castilla’s usual home turf. Up to then, entrance for 2nd Division matches was free, but when the club realised that the space for around 5,000 supporters was way more than full for every single match, they started to charge for admission. It did not deter the fans, as the sold- out sign kept appearing: The show was well worth it. At that point, the club decided to move all of Castilla matches to the Santiago Bernabeu itself. They never regretted it.

That season, Castilla competed neck and neck with Bilbao Athletic, the confusingly named youth team of Athletic de Bilbao, where a certain Julio Salinas scored more often than not. Thus, the visit of the Bilbaínos to Madrid in November sounded like a huge occasion. Even though expectations were high, a shocking 63.000 people – a really young version of myself among them – turned up to root for Castilla that evening.

The 4-1 demolition of Bilbao Athletic still ranks very high in my football memories. The same socios that used to bitch about the first team’s performances match after match were also there, metamorphosed into supporters who behaved as though they were thirty years younger, showing a childish excitement that surprised me even more than the then decrepit Bernabeu at 70% capacity to watch a bunch of teenagers. Something was really happening with the youth team.

Trained by Real Madrid legend Amancio Amaro, winner of the 1966 European Cup as a player, that version of Castilla devoted all its energy and skill into feeding a short, blondish forward with the face of a child and an amazing ability to fool his markers inside the box. Emilio Butragueño, nicknamed ‘Buitre’ because of the similarity of his last name with the Spanish word for vulture, was the leader of that team, the unpredictable factor who could finish off a match in five minutes of inspiration.

His short stature had made things difficult for him at the beginning. Real Madrid rejected him initially, pushing him to consider playing for Atletico and even training with them for a few days. One night, his die-hard madridista father, a socio (member) who had made Emilio a socio on the same day he was born, went to his room and asked him: “Son, how one earth are you going to play for Atletico? I can’t let you do that”. Mr Butragueño took the matter into his own hands, pulled a few strings and arranged another test for young Emilio. He would play for the Merengues for the next 14 years.

In any case, that convincing win over Bilbao Athletic had settled it for good: Emilio Butragueño and his class had to be promoted to the first team immediately. And that’s exactly what happened.

2) 5th of February, 1984. Cadiz 2 – 3 Real Madrid: the perfect debut.

Surprisingly enough, the high-flying Buitre was not the first player of his own Quinta to make his debut with the first team. With forwards Juan Gómez “Juanito” and Carlos Alonso “Santillana” providing plenty of offensive edge, the squad required more midfielders than strikers. Manuel Sanchís – a classy centre back who could also play defensive midfield – and Rafael Martín Vázquez – an incredibly ambidextrous offensive midfielder – got the nod to play for Real Madrid in the Primera División two months earlier than Butragueño did. Both performed well, Sanchís even scoring the winner versus Murcia.

But the hype about el Buitre and his feats with Castilla kept growing as the season went along, so first team coach and Real Madrid legend Alfredo Di Stéfano decided to shake things up a little bit up front too, and Butragueño eventually made the squad for a league trip to Cádiz.

With Real Madrid 2-0 down at halftime and a depressed Eduardo listening to the match at the loudest volume possible on his old Sanyo, the coach said the words that started a memorable era for the merengues: “Nene, calentá!”(“Kid, warm up!” with a heavy Argentinean accent).

Santillana then left his place on the team for the kid – the actual nickname of El Buitre among his teammates was ‘el Niño’ – and watched in amazement as the newcomer turned the match upside down. Two goals and an assist in 45 minutes gave Real Madrid a famous win and put Butragueño on the Primera Division map.

Ecstatic with the victory, I asked – and was granted – special permission to watch the Spanish, late night version of Match of the Day to actually see what Butragueño had done in Cadiz, and listen to what he had to say about it. The feeling that something singular had in fact happened kept me awake for a few hours, although I must admit that the first interview of my new idol on national TV also left me slightly confused: he mentioned Johann Cruyff as his biggest football reference. Yes, Barcelona’s Johann Cruyff.

Oh well. It would take the remaining two members – Pardeza and Michel, a few more months to play for the first team, but the Quinta del Buitre, a term famously coined by Spanish journalist Julio Cesar Iglesias meaning the Class of the Vulture/Vulture Squadron, had finally made it big.

3) 12th of December, 1984. Real Madrid 6 – 1 Anderlecht: the era of the comebacks is born.

The promotion of the whole Quinta to the Primera División squad created a fantastic mixture between incumbents – seasoned players like Jose Antonio Camacho and Miguel Porlán “Chendo”, who never gave up on any ball, play or match but who were technically average – and newcomers, who played with flair and classy abandon even when they were behind on the scoresheet.

That combination between guts and class became perfect during the consecutive UEFA Cups won by Real Madrid in 85 and 86, almost twenty years after their last European title. No matter how poor the result had been in the away leg, every Madridista in the city knew it would be turned around at the Bernabeu, with the lucky South End goal as the preferred location to stage the comeback.

During those two seasons, the Merengues managed to overcome deficits of two goals or more in eight different knock-out rounds, thus eliminating opponents such as Internazionale de Milan (twice), Borussia Monchengladbach or AEK Athens. However, the most memorable encounter happened against RSC Anderlecht.

At that time, the Belgians had put together a fantastic squad, which featured a very young Vincenzo Scifo, plus legends such as Morten Olsen and Frank Arnesen at the top of their game. Reigning champions of the UEFA Cup at that point, they had just eliminated Socrates’ Fiorentina with ease in the previous round, scoring six times in the return match in Brussels.

In their first leg against Real Madrid they picked up where they had left off with Viola. 3-0, with all the goals scored in the last twenty minutes and the rewarding feeling of a job well done. Indeed, they thought it was all over.

Anderlecht’s stuttering display in the return match saw Jorge Valdano employ a psychological term to describe what most teams went through when they visited the Bernabeu in one of those European comebacks: “Miedo Escénico” (stage fright). No one could fail to feel intimidated by the almost demented way in which both players and supporters did their respective bits for each of those miracles to happen. The electric atmosphere in the stands where a collection of characters – nowadays priced out of the stadium – screamed expletives and sang non-stop, still make many of us long for those magical nights. But in my memories, and bizarre though it may sound, it was the fans who fed off the amazing intensity of the players, and not the other way around. Most supporters went mad watching all eleven starters play like possessed men, something especially remarkable in the case of Míchel, in his own right one of the classiest wingers ever to play in Spain, but who only on these occasions found the correct amount of stamina to go with his deadly right foot.

In this match, the scared-to-death Belgians conceded four times in the first 38 minutes, plus two more in the first five minutes of the second half. Their 6-1 defeat, coupled with Butragueño’s first hat trick for the first team, showed that no comeback was too far-fetched for this team, even in Europe.

4) 25th of November, 1989: Real Madrid 7 – 2 Zaragoza – The scoring machine.

The apex of the revolution that the Quinta del Buitre signified in terms of offensive football in Spain took place during the 1989-1990 season, under the sarcastic but firm command of Welshman John Benjamin Toshack. In what would become their fifth league title in a row, the Madridistas delighted every single football fan – yes, even quite a few Cules – with weekly displays of fast, thrilling football. No goal difference was enough: the squad would keep trying to score once more, as even bench players such as Adolfo Aldana or Sebastián Losada often chipped in with a goal or two. The sole destination of the ball was the goal line; the sole point of possession was to strike as often as possible.

In previous seasons, the club had added some reinforcements that progressively gelled and took the Quinta’s usual flair to new heights of offensive efficiency: German playmaker Bernd Schuster – signed from Barcelona in 1988 after a fantastic coup by Real Madrid’s president Ramon Mendoza; left winger Rafael Gordillo, a master of getting to the goal line for a fatal cross; Antonio Maceda, a firm centreback who could also score off set pieces; and last, but definitely not least, Hugo Sánchez, the Mexican striker who had been “stolen” from neighbours Atletico by who else but Mr Mendoza in the summer of 1985. Hugo himself coined the term “Quinta de los Machos” (Macho Squadron) for the four aforementioned signings, stating more than once that the Quinta del Buitre would have never reached those levels of offensive excellence without their help. He was probably right.

In the 89-90 season, ‘Hugol’, as he was known by the Real Madrid faithful, scored 38 times in 38 matches, all of them off a single touch, never taking the time to stop the ball even once. The feat speaks highly not only of Hugo’s uncanny ability to strike in almost any circumstance, but also of the team’s skill to leave their number 9 in front of the goal time after time, not having him go through the trouble of dribbling defenders or the keeper at all.

Regardless of who did the most for the machine to work, it performed beyond excellence. The 89-90 season saw Real Madrid ridicule their opponents more often that not. The team broke the scoring record with 107 goals in 38 matches, a number never approached by Cruyff’s ultra-offensive Barcelona and only surpassed in the current era, in which the abyss between the top two and the rest has widened to worrying extremes.

Several matches from that season aptly exemplify the relentless “Let’s score one more” attitude of the squad. However, the 7-2 demolition of Real Zaragoza at the Bernabeu, a football orgy if there was ever one, against a usually decent rival who finished the league in 8th position, deserves special recognition (see from min 5:05 of this video). El País, a usually balanced newspaper, titled its chronicle “The best of their repertoire” the following day, describing at length and in an almost giddy way five of the seven goals.

Ironically, fifth man of the Quinta Miguel Pardeza played for Zaragoza that evening. He had left the club in 1987, as the unstoppable duo of Hugol and El Buitre monopolised every single start. That night, he suffered a special dose of his former mates at their emphatic best.

In a season that became probably the best ever for several players in the team, one shone above the rest; this match showcased his stunning skill with both legs, be it dribbling, crossing or shooting on goal. Rafael Martín Vázquez, scorer of 15 goals that year – at least 10 of them golazos – became at that point the most complete offensive midfielder in the country, one of the best in Europe and for some inexplicable reason, my favourite player of all time. Against Zaragoza, Martín Vazquez scored twice and assisted in three other goals.

Real Madrid could have scored 12 and no spectator would have been surprised.

5) 18th of October, 1989: AC Milan 2 – 0 Real Madrid. The end

Having won the UEFA Cup twice in their early years, the European Cup became the Quinta’s biggest obsession, but they kept falling painfully short. Despite the new signings every season, the special preparation and the support of the public, Butragueño and company were defeated three years in a row in the semifinal round against Bayern Munich, PSV Eindhoven and AC Milan respectively. In all truth, they deserved better against the Dutch side, but were defeated fairly in the other two contests. Their flair had delivered them La Liga every year, but they lacked some extra physicality to get over the hump of the semis in the biggest European competition.

In 1989, their early exit in the second round, again at the hands of the devastating AC Milan, became the final nail in the coffin of this extraordinarily successful generation of players, at least in terms of a real challenge for European silverware as a group. At the end of the season, Rafael Martín Vázquez decided to leave for Torino after months discussing a new contract with President Mendoza. Even though he returned to the Bernabeu two seasons later, he’d never reach the same heights of performance again, and the chance to further exploit the potential of the Quinta evaporated.

In the following seasons, the Quinta would lose two consecutive ligas in the final match against Cruyff’s Barcelona, to then win their last title together in the 94-95 season, with former team mate Jorge Valdano as coach.

I remember well the last official goal of Butragueño at the Bernabéu, in a 3-1 win over Racing de Santander in which Martín Vázquez also scored, still in the first half of that farewell league. That Real Madrid already belonged to Raúl González, who took the reins from the Quinta with firm hands.

Butragueño and Martín Vázquez would leave that summer for good, while Míchel would remain for one more season. Sanchis, loyal until the end, would become the only member of the Quinta to finally win the Champions League title, in the 97-98 and the 99-00 seasons, and would retire without ever having worn a shirt other than that of Real Madrid.

Epilogue: Where are they now

Emilio Butragueño is Real Madrid’s VP for PR. Still looks younger than most first team players, and is widely remember for this beauty.

Rafael Martín Vazquez provides the colourful comments for Radio Marca.

Jose Miguel González “Míchel” works as a coach. His last team was Malaga.

Manuel Sanchís manages his private investments. Many see him as a future candidate for Real Madrid’s presidency.

Miguel Pardeza worked as a Sports Director of Real Madrid until July of 2014. He’s a decent writer.

Muy bien señor Alvarez! Even though I’m a Barça fan, thanks to señor Pelota’s Morbo y Tormento Blanco, I’ve always had a soft corner for Madrid. I mean I enjoy the schadenfreude when Madrid lose or suffer but I don’t really hate them. In fact, before Cristiano joined Madrid, I’d actively cheer Madrid in UCL cos I’ve always wanted teams from Spain to do well. Now that he’s gone, I wouldn’t mind Madrid winning a 4th in a row, if Barça get eliminated (seems a very likely thing to happen thanks to Valverde’s no-rotation policy & the sieve that is Barça defence) early.

Back to those books. It was in those books that I’d learnt the word “remontada” & Juanito’s famous “90 minutes last longer in Bernabeu”. Have always been jealous of Madrid’s high octane aggressive play whenever they’re down. Other than the 6-1 win against PSG, that Iniesta goal at the Bridge & Messi’s jersey goal, Barça don’t really do the “lay siege to opposition goal & score a 95th minute winner” thingamajig.

Really enjoyed reading this piece. I’m also shamelessly claiming a teensy bit of credit for giving this idea at the end of last season 😛 :D. Hope there are more such pieces in the future.

LikeLike

LOL, thank you very much. In fact, I’d written most of the piece for the launch of a website that never happened a couple of seasons ago. You reminded me of it. Glad you enjoyed it

LikeLike

“before Cristiano joined Madrid, I’d actively cheer Madrid in UCL cos I’ve always wanted teams from Spain to do well”

Me too! Thought I was the only Barca fan like this. I don’t remember when my attitude changed, but it had more to do with RM fans where I live than anything the players or club were doing. Whenever my attitude changed and whatever the reason, Mou’s arrival cemented the change for me.

LikeLike

Thanks for the YouTube links. It’s remarkable that a youth team went from free attendance to selling 63,000 tickets for a match. I’m not aware of any equivalent since. All this history gives even more credit–not that I needed it–to your analysis of current matters. Seeing Teka in some of the above images makes me recall Kelme and the 90s. And I’m still reading into and making some assumptions about the regular comments like “nowadays priced out of the stadium”. I suspect Phil and/or you could put together quite the social-political-sporting piece about the globalization and business side of clubs and leagues. Finally, love the usual dose of humor: “…came back from Italy with that mustache”. Great caption!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s borderline infuriating past the point of annoyance that they never commemorated their excellence with a proper European title. Had they nabbed a cup or two under their belts I have a feeling they’d easily be mentioned among the great squads in the history of the sport. Very nice read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gran trabajo Ed! Forgive my attempt at Spanish but this piece is really piece de resistance. I am big sucker for nostalgic, reflective, meditative writing on sports in general and futebol most obviously! A chance to travel back in time, relish and have a new appreciation. I could only follow Leagues in 80’s through papers and Buitre made a quinta flash at 86 World Cup! When scoring 20+ goals in a season seemed a brilliant achievement Hugo’s scoring feats made them near mythical…..with zero video footage my imagination ran riot. I knew of this team a lil bit and felt gratified that Buitre had a successful nigh brilliant career other than 5 goal salvo in WC. You know what I’ll be watching on YT for the next several days….

Thanks for the maravilloso piece Ed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Bala! Really enjoyed writing this one

LikeLike

Martin Vazquez’ mustache – Also known as an 80s pornstar mustache

I fully enjoyed reading this not just for the piece of history I didn’t know existed, but because of how well written it was.

Couldn’t help but wonder how Spain’s national team was performing during that time…

LikeLiked by 1 person